In 1920, James Weldon Johnson, former U.S. consul in Venezuela and Guatemala and later executive secretary of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, published an article in The Nation entitled “Self-Determining Haiti,” containing the section “The Truth about the Conquest of Haiti,” a critical rebuke of the U.S. occupation of Haiti, which had begun in 1915 and would continue a full fourteen years after Johnson’s article was published. Throughout the piece, he expresses a view of the U.S. occupiers as aloof from and disdainful of the Haitians they governed, and of their Occupation as wholly unnecessary; a dangerous force acting to spread American racial prejudices to Haiti.

Among a variety of examples, Johnson mentions the replacement of the Haitian legislative body with a “Council of State” that was essentially an Occupation puppet, and the fact that the government of Haiti was forced to pay for automobiles for certain Occupation officials, while its own members had to either provide their own or go without—both of which demonstrate a severe lack of regard for the Haitian government on the part of the U.S. Occupiers. The document also demonstrates the author’s strong view that the U.S. Occupation was unnecessary; of particular note, he writes that, “ … The military Occupation has made and continues to make military Occupation necessary” (125), and explains how much of the disorder requiring a military presence to maintain the law was caused by that very same military presence—the Occupation, in his view, justified itself using circular logic. Additionally, he claims that the Occupation benefitted Haiti solely in that it resulted in urban sanitation measures, an unspecified “improvement” of a single hospital, and the construction of a central highway, of which the two former could have been obtained just as easily through the efforts of non-military, and presumably Haitian, organizations, while the latter was itself another example of something like circular reasoning, being (according to Johnson) intended more for transportation of Occupation troops than for ease of civilian travel. Furthermore, the Occupation constructed this road using Haitian forced labor, which Johnson characterizes as a type of short-term slavery, owing to the harsh working and living conditions forced upon the Haitian workers—yet another sign of the complete lack of respect for the very people the Occupation claimed to be protecting.

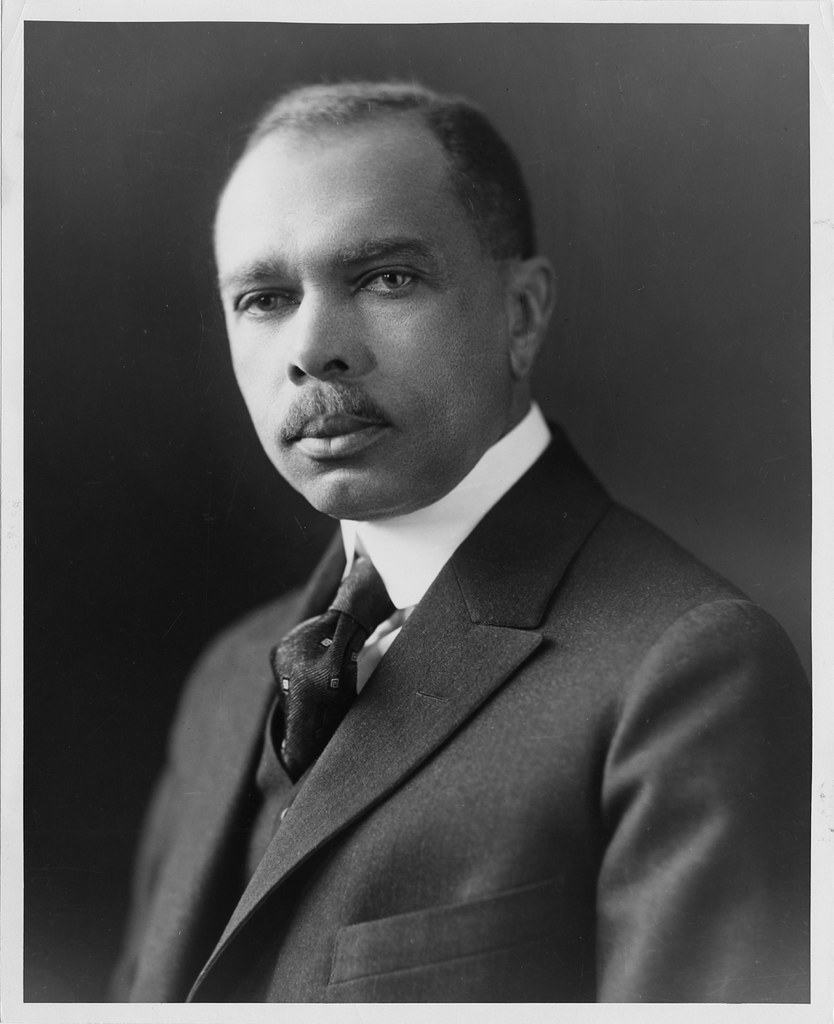

The views that Johnson presents in the article are an example of something rather unusual in early-twentieth-century U.S. political writing—a major voice from the U.S. not only calling for an end to his country’s imperialistic endeavors, but doing so wholly for the sake of those being subjected to American domination. At the same time, Johnson, himself Black, came from a historically oppressed background, but rose to a position of some prominence, first as a U.S. diplomat and afterwards as the executive secretary of the NAACP, so his writing of the article in question also provides an example of how people from such situations have used their power to try to help other marginalized groups, and at the same time perhaps explains why his views were contrary to those of more mainstream, imperialistic U.S attitudes of the early twentieth century.

Johnson, James Weldon. “The Truth about the Conquest of Haiti” from “Self-Determining Haiti”. In American Empire at the Turn of the Twentieth Century, edited by Kristin L. Hoganson. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2017.