In Edith Moses’ collection of letters detailing her view of the Filipino people, Moses argues that the Filipino people are simply and friendly, with characteristics similar to children. The set of letters were written by Moses between 1900 and 1908. Moses largely understood her role in the Philippines as a social scientist and a reminder of traditional western values. Moses and her husband were sent to the Philippines to help establish citizen governments as part of the United States’ Second Philippine Commission in Manila, also known as the Taft Commission.

The United States began to directly intervene in the Philippines in 1898, attempting to seize colonial control of the islands from the Spanish. By 1899, the US and Spain had settled disputes, handing control of the islands over to American hands. The Philippines, attempting to emerge as an independent state, resisted the onset of US imperial rule. As a result of the United States’ self-proclaimed authority over the Philippines, Americans began to move to the newest US colony to establish American presence and governance on the islands. While governing the Philippines, the United States employed a variety of policies regarding education, public health, and economic production.

Edith Moses, in her earliest letters, discusses the process of establishing colonial influence and American society on a domestic level. Moses tends to infantilize the Filipinos she interacted with, and she claims that the Filipinos are much less “violent” than they are typically depicted as by other American colonists. Moses largely depicts the Filipinos as rather unintelligent, but hardworking, people. Concerned about the cholera outbreak at the time, Edith Moses wrote about the measures the colonial government took to prevent its spread. Moses references colonial measures that moved infected Filipinos to detention camps and burnt nipa huts of infected peoples.

Manila, June 11, 1900

Last week we began cleaning and painting, and ever since our house has been full of Filipinos who have somehow become part of our household in this easy-going place. I have gained quite an insight into native character through this experience. The Filipinos are like children and love to do everything but the thing they are set to do. They run to assist the house boys in their work; they advise me about arranging my furniture; and insist upon unpacking china when they are hired to paint the walls. They are always playing tricks on each other, and are unfailingly good-natured, but the painting progresses very slowly; often they disappear altogether, but come back again smiling next day, explaining it was a fiesta. From an ethnological standpoint this is all interesting, but I can imagine that here is displayed one of the race characteristics, which, after the novelty is gone, “weareth the Christian down.” . . .. . . Manila is a tranquil city. Political affairs are much more encouraging than they seemed to be when we left America. All organized resistance is over. There are a great many bandits and robbers, but every day they are being captured and their ammunition discovered. The dreaded rainy season is worse for the Filipinos than for our men, for now we hold all the towns and they are “chasing themselves around the country,” as a young officer put it. They do not seem to be such a fierce race as they are reported. They strike me as lazy, polite, and good-natured. They may be treacherous, and everyone says they are, but on the surface the lower classes are certainly very agreeable.

We have a neighbor opposite who lives in a nipa hut.1 He has a wife and two children, and is a fisherman. Once or twice we have thrown candy out of the window to the children. Last Sunday morning the little girl came up the stairway leading her small brother by the hand. He wore a gauze shirt that came about two inches below his armpits. The little girl wore a pink calico chemise and carried in her hand a plate of fresh crabs. This was a gift in return for the candy. I offered to pay for them but she ran away, shaking her head. . . .

Manila, March 23, 1902

I suppose the correspondents have telegraphed to America the news of the outbreak of cholera, and that you are imagining all sorts of horrors. The fact is that after the first uncertainty — during the days when the authorities suspected its existence, but were hoping the disease would be sporadic — we were all more or less nervous, but now that we know that Manila is really in for a siege of cholera, everyone has calmed down, and is hard at work making the town as sanitary as possible. The excitement attending so serious a situation as the outbreak of cholera, in a city in which only a few years ago thirty thousand persons perished within three months, keeps one from taking time to be frightened. . . . We hosed off the “China” boys and Filipinos with disinfectants, and I made their eyes stick out with fright by describing a cholera germ. . . . Of course, we eat only tinned vegetables and well-done meats, but in addition we toast all the bread, heat all the plates, and scald all the glasses before every meal. We open a fresh tin of cream each meal, and have concluded to buy tinned butter. The water is distilled, and the bottles in which we keep it sterilized. This means continuous oversight, and at night I am so tired that I have no time to let my imagination run riot.The Commission is holding extra sessions, and everyone is working to prevent the spread of the disease, and get the city in as sanitary a condition as possible. It has been divided into districts, in each of which there is a chief surgeon, under whom are doctors, inspectors, police, and helpers. There is a house-to-house inspection, and the nipa shacks in which deaths occur are to be burned, because the nipa hut cannot be properly disinfected. The government will pay the owners for the property destroyed. A detention camp has been built outside the city, where it is proposed to detain the inmates of the houses where a death from cholera has occurred. This quarantine camp is regarded with suspicion by the natives, who imagine all kinds of horrors await them there. It is difficult to manage the lowest classes, who are the ones at present in the greatest danger. They instinctively hide their sick, and do everything to avoid a quarantine. Even intelligent Filipinos are disposed to conceal the fact that a member of their family has cholera. One reason is the prohibition of funerals, and the fear of cremation, which they seem to think will send them straight to perdition.

Manila, April 4, 1902

Edith Moses in an excerpt from “Unofficial Letters from an Official’s Wife” (1908)

. . . . We are still fighting the cholera, but, as the natives persist in hiding the sick, the number of cases is increasing. The Board of Health is burning whole districts where the shacks are in a filthy condition. It is hard for the natives; they are bewildered, and cannot understand the reason for it. Some one said the other night that the natives were more afraid of the sanitary inspector than of the cholera. Sometimes, when I think of our rough ways of doing things, I feel an intense pity for these poor people, who are being what we call “civilized” by main force. Of course, in the cholera time it is for their immediate good, and the government pays for their houses and their goods, yet they cannot understand it, and it seems an act of tyranny worse than that of the Spaniards.

Sources:

Moses, Edith. “Edith Moses: The Filipinos Are Like Children 1908.” In American Empire at the Turn of the Twentieth Century: A Brief History with Documents, edited by Kristin L. Hoganson, 121–23. Macmillan Higher Education, 2017.

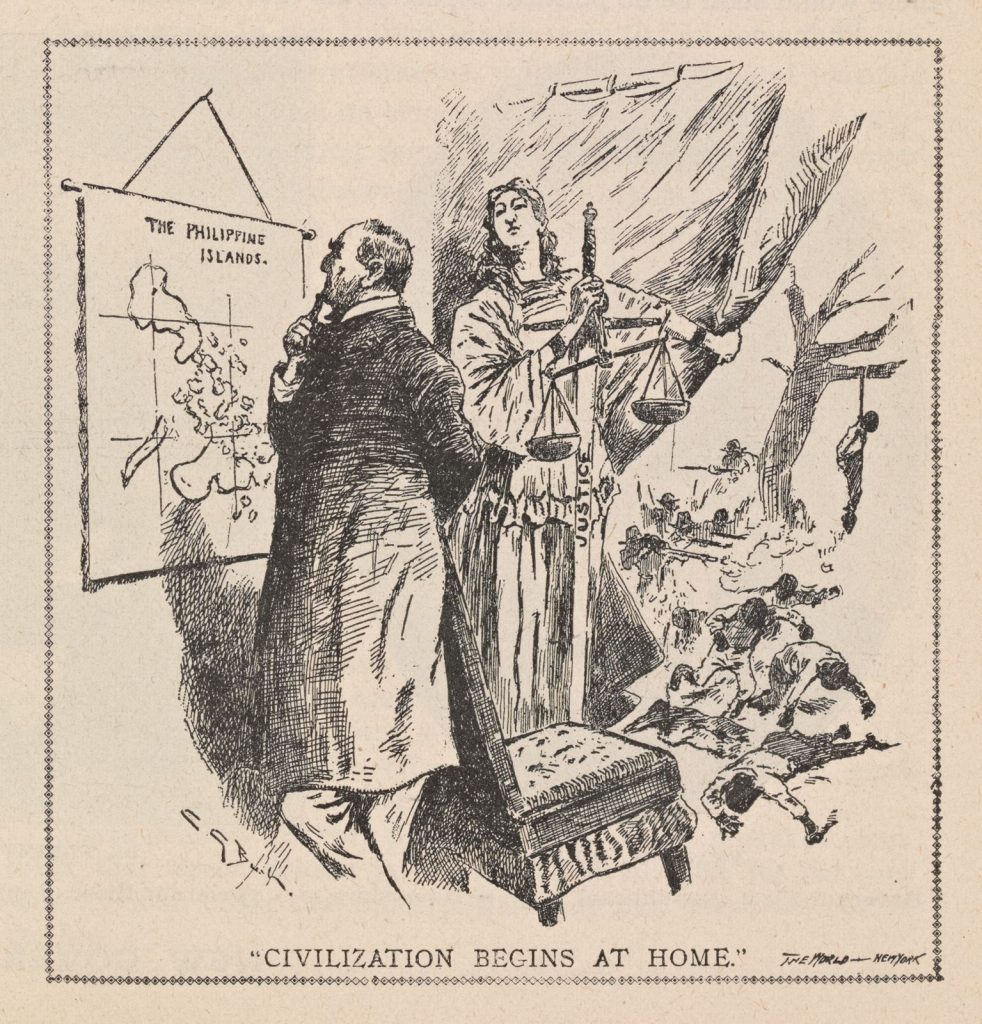

General Research Division, The New York Public Library. “”Civilization begins at home.”” New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed October 26, 2022. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/b3ffb660-4254-c9e4-e040-e00a18067733